Consumer-focused health websites are terrible—but the tide is changing

Secular trends in publishing models, open access research, and AI are finally making it feasible to give patients the health information they need.

I'm health website connoisseur. And here's the tl;dr for health websites in 2022: they're all terrible.

So I was pretty shocked when—three days ago—somebody showed me an amazing health website. It was user-friendly, evidence-based, and gave clear, actionable advice. Instead of assaulting you with ads and pop-ups, It answered your questions and helped you make important health-related decisions. It evoked trust and clarity and healthfulness. It was called DynaMed Decisions.

The first thing that caught my eye was their breast cancer screening guide. Unlike most health websites, DynaMed understands that you're here to make a decision, and the whole page is framed around a single decision in particular: Should I get a mammogram?

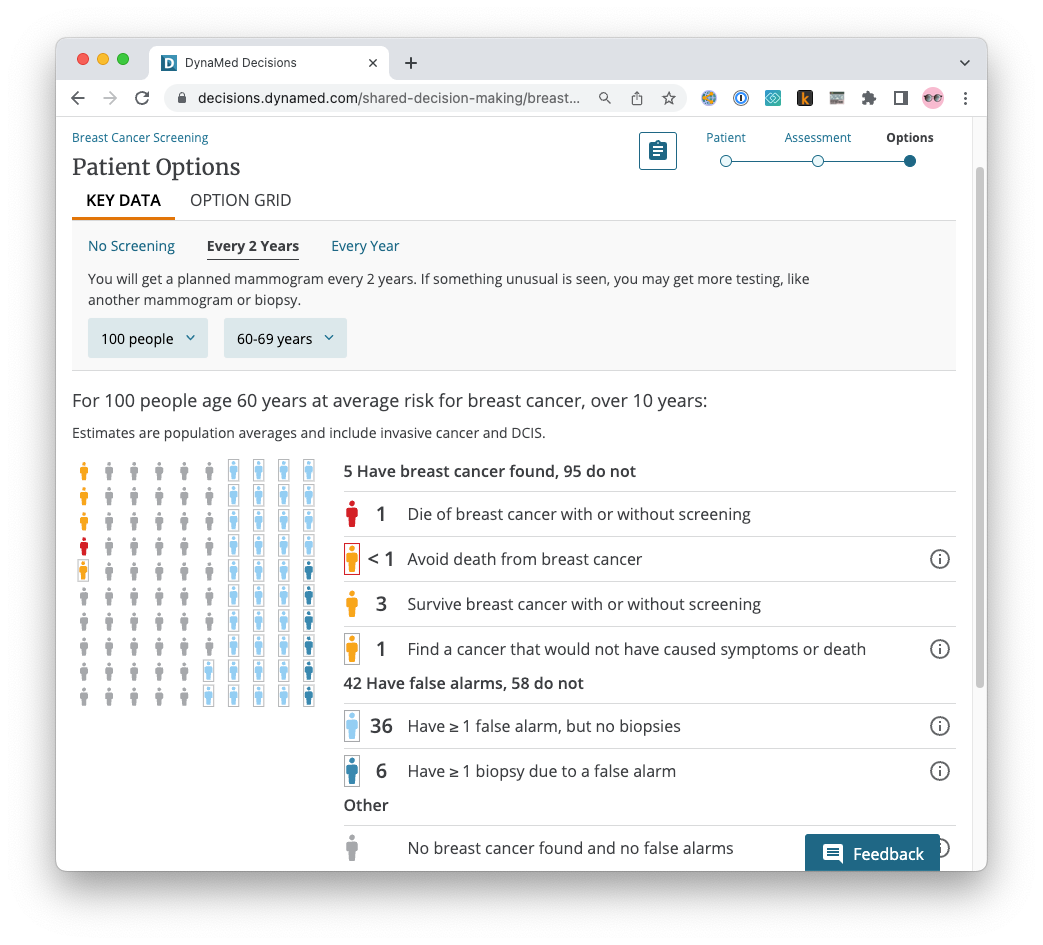

After answering a few questions, I'm immediately presented with an awesome visualization of the probability of different outcomes for people who do and don't get mammograms:

Understanding the probabilities involved in something like cancer screening is really hard, even for doctors—yet this simple diagram makes it super obvious. And if that wasn't clear enough, all my important questions are answered with regard to every possible choice:

If you aren't blown away by these screenshots then you haven't spent much time trawling WebMD, Healthline, or even the more reputable (but equally unhelpful) government health websites. Clear, concrete, evidence-based advice is really hard to come by on the internet.

Hungry for more, I click on "Flu Vaccine: Should I get it?" because hey it's almost flu season and I've been meaning—

The paywall slaps me in the face. I sit there for a second, stunned.

But slowly I recover my senses. You know what? Maybe it is worth it. My health is really important, and if this resource helps me live a healthier life then honestly I'd be willing to shell out—

I spit-take my coffee all over my screen. Request a demo?

Ugh. We all know that "request a demo" is landing-page-speak for "you're a schmuck and you can't afford this enterprise software."

What's happening here? This whole time the tool was talking to me, the patient—e.g. "...your risk of breast cancer…"—not to my physician. So why is this awesome patient-focused website making it impossible for patients to use it?

Patients are terrible customers

The answer, of course, is money. DynaMed can get a lot more money from your doctor than they can get from you. So they designed DynaMed decisions to be accessed by your doctor, on their iPad, while sitting next to a patient.

It turns out that hospitals and medical groups have several big incentives to pay for good health information

Their health care staff need to satisfy training and continuing education requirements (CME, MOC, etc.)

They're rated on certain patient outcomes (e.g. HAC scores) that need to stay above a certain level

It makes their staff more efficient, which brings down costs

So most hospitals decide it's worth it to spend $399/year per doctor for access to DynaMed. And that insane price tag lets EBSCO (DynaMed's parent company) spend a lot of money on delivering high-quality health information with great UX.

But consumers? Most of us aren't willing to shell out a fraction of that for health information. So instead, we're left with the dregs: a mishmash of vague, ass-covering statements from WebMD, scant information from public health officials, and a cacophony of outrageous claims from people trying to build their #wellness audiences.

And DynaMed is the cheap option. Their larger competitor, UpToDate, charges a whopping $696/year ($58/month) per doctor. But it's really good. Just compare their (free) article on depression management to WebMD's page on depression treatments. While WebMD does mention some of the same treatments, it's missing the practical guidelines, the supporting evidence, and the detailed discussion of tradeoffs. You can't really make any sort of health decision using the WebMD article—its only purpose is to rank highly on Google and not ruffle any feathers. What's great about UpToDate and DynaMed is that they're decision-making tools—and decision-making is why people Google their health problems in the first place!

The existence of DynaMed and UpToDate prove one thing: consumer health information could be so much better.

Good health information is just out of reach

So here's the reality we find ourselves in:

There's a treasure trove of high-quality, evidence-based, practical health information available on the internet

This health information could dramatically improve your life

The only way to see it is to borrow your doctor's iPad

It boils my blood. Is there nothing to be done?

3 trends are making health information more profitable

Despite the depressing reality of health information economics, I think building a consumer-focused health reference is getting more and more feasible every day. Three secular trends are providing some serious tailwinds: new publishing models, more open access research, and major advances in AI.

New publishing models

It's tough to remember, but ten years ago nobody paid for information on the internet. If you pulled out your credit card in front of your computer it was because you were buying something physical. But these days we're all used to paying for good information—it's common to have subscriptions to the New York Times, Consumer Reports, podcasts, and any number of niche Substacks.

Despite this trend, today's popular medical sites are still stuck in the past: WebMD, Healthline, Everyday Health, and the rest are all ad-supported. This works when you've reached the scale that these companies operate at, but an ad-based model is really hard to bootstrap—which might explain the dearth of new WebMD competitors!

But the subscription model gives me hope. Platforms like Substack have shown us it's possible to make quite a bit of money focusing on very niche topics—which would enable an upstart to start with a specific topic and slowly expand to eventually cover all health topics.

More open access research

The open access research movement is gaining serious momentum. Since 2015, over half of newly-published medical research is open access. "Open access" means that the costs of publication are borne by other parties (research institutions, nonprofits, governments, etc.) and not by the reader. This is already a good trend for consumers!

But it's also good for anyone trying to distribute high quality health information. The raw inputs to a health reference site are peer-reviewed medical studies—and if these inputs are free then the cost of producing these references is significantly reduced.

Rapid improvements in AI

As mentioned above, the typical publishing process for a reference like UpToDate involves paying a highly-credentialed expert to spend hours diving into primary research and writing a long-form article about a topic. This is a very expensive way to turn primary research into useful health information.

I believe there will always be experts involved in the generation of medical references. But the rise of large language models and other AI techniques have made it possible to automate the most tedious parts of these reviews, like searching for all relevant studies, screening out irrelevant studies, extracting key information, and synthesizing that information into summary statistics.

AI's recent progress is staggering. Five years ago there was no robust way to extract key information from free-text studies. Today, you can literally ask GPT-3 to "Extract p-value, standard error, outcomes measures, and sample size from the following study…" and it'll do it in a couple seconds (see Elicit.org for a great example of using AI for this purpose).

This kind of automation can vastly reduce the cost of producing high-quality health information.

Making it all work

Previously, it wasn't profitable to deliver physician-quality health information to patients. But the trends above make me hopeful that we've reached a tipping point where it's just become possible to do it. Open access journals and AI make it cheaper to produce this information, and subscription-based models make it easier to bootstrap an information-based business.

But do we really need better health information?

We deserve better

I think there's a sort of learned helplessness when it comes to online health information. Everyone knows that the big health websites are terrible. But I think we have this idea that health is complicated, and providing useful health information at scale is impossible.

But the existence of DynaMed and UpToDate make it clear that it is possible. It literally already exists. We just need to get it to the people that need it the most.

I'm serious about solving this problem, so last Friday I quit my job so I could try and figure this all out. Building a better WebMD definitely won't be easy—but hopefully I've convinced you that it's possible. I'm doing my damndest to take advantage of the trends mentioned above, and I'll keep this Substack updated with the progress.

You can check out the (humble!) beginnings here: https://www.longcovidstudies.org

Ideas? Questions? Feedback? Try me on Twitter: @tomjcleveland