Medical communication is bad—how do we fix it?

A jeremiad against current online health information and a proposal for fixing it

Short on time? Skip the diatribe and check out my demo.

I’ve said it before: online health information is bad. Here’s me in 2019 complaining about the terrible search results for over-the-counter painkillers:

If you’re among the 77% of Americans that Google their health problems, insipid answers like this won’t surprise you. But we should be surprised, because researchers carry out tens of thousands of clinical trials every year. And hundreds of clinical trials have examined the effectiveness of painkillers. So why can’t I easily Google those results?

Then COVID-19 happened. As much as the painkiller information annoyed me, it was leagues better than the information we started getting about COVID prevention and treatment.

The pandemic created conditions where (1) everyone was searching the internet for COVID-related health information and (2) the science on COVID prevention and treatment changed quickly. This created a COVID information ecosystem that was so balkanized and fluid that even my homogenous group of friends had drastically different views on mask wearing, social distancing, vaccines, treatments, and risks.

“I believe in science,” one of my friends said, smugly.

That’s wonderful, I thought, but which science?

Of course what most people mean when they say “I believe in science” is “I believe in scientists,”—or, more often, in journalists or politicians who claim to be “following the science.”

And this is why science has become so politicized. The Enlightenment ideal of science was that it was so pure and objective that it couldn’t be politicized—there was no arguing with empirical observation! But in reality 99.999% of people aren’t running their own randomized controlled trials on COVID vaccines and observing the results. In fact, 99.999% of people aren’t even reading the published results from vaccine trials. Instead, most people read headlines or tweets authored by someone who read a summary of an official statement based on a summary of a review of a published result. And that’s where politics can creep in.

You read a headline: “Pfizer vaccine is 96% effective at preventing COVID-19.” You immediately book your vaccine appointment and start celebrating. But a couple days later a friend looks horrified when you tell her you’re getting a vaccine.

“The Pfizer vaccine? Didn’t you read about the myocarditis stuff?”

So you Google “covid vaccine myocarditis” and suddenly you’re waist deep in a rabbit hole. You read peer-reviewed papers about increased heart-swelling in some vaccine recipients. You scan scary-looking myocarditis data from the Vaccine Adverse Events Reporting System (VAERS), which is published by a government body. You watch countless YouTube videos from licensed physicians urging people to avoid COVID vaccines. If “believing in science” means “believing in credentialed scientists,” then you have a problem—they don’t agree!

And this is where politics comes in. If you’re someone who trusts the government, mainstream news, and academia, then you’ll probably side with the pro-vaccine people. If you’re someone who distrusts these groups, then you’ll say, “Well, I’m hearing different things, but the people I trust say the vaccine is dangerous, so I might as well hold off and see how this shakes out.”

And that’s pretty reasonable! For the record, I absolutely think that the benefits of COVID vaccines outweigh the risks—but my point is that I very much empathize with the people who see lots of apparently contradictory information about novel injections and get a little skittish.

The only reason I'm so confident about vaccines is that I have the time and statistical literacy to read a bunch of the primary literature. I know about the limitations of VAERS data; I know the relative risks of myocarditis vs. COVID complications; I can quantify vaccine efficacy over time. In short: I know how to put all of these seemingly-conflicting medical claims in a context that resolves the conflict and points to a fairly clear conclusion.

But most people don’t have the time or background knowledge to do this. And they shouldn’t have to! The problem is that medical communication today is really bad.

To see what I mean, let’s start by talking about good medical communication. Good medical communication, I want to argue, has three attributes:

It’s quantitative

It’s exhaustive

And it’s accessible

Let’s take each of these in turn.

Good medical communication is quantitative, because qualitative data is useless for making real-world decisions. For example, the Mayo Clinic has an article titled How well do face masks protect against COVID-19? in which they answer the titular question with this zinger:

Face masks combined with other preventive measures, such as getting vaccinated, frequent hand-washing and physical distancing, can help slow the spread of the virus that causes COVID-19.

There is precisely zero information in that sentence. You could replace the phrase “face masks” with “shrimp gumbo” and that sentence would still be 100% accurate. If all you can tell me about masks is that, combined with other measures, they can slow the spread of COVID-19—that's not very compelling! Give me a number! Quantify the effectiveness of mask wearing by itself! If you tell me masks reduce my odds of getting COVID by 50%, then of course I'll wear a mask. But if it's only 0.05% then maybe I won’t bother. Numbers matter.

But quantitative data alone isn't enough—good medical communication is also exhaustive. By "exhaustive" I mean that it includes all research on a given topic. Exhaustive communication bolsters your argument ("look at all this data!") and helps undermine counterarguments ("we know about the conflicting data, but here's why it doesn't matter").

At first glance, this BBC article appears to thoroughly debunk the use of Ivermectin for treating COVID-19. It says that of the 26 "major" Ivermectin trials, one third have statistical errors or indications of fraud, and the other two thirds don't support the use of Ivermectin.

But then someone on Twitter links you to ivmmeta.com and, boy, these people do not mince words:

The [BBC] article reports that 26 studies were examined, however there are 79 studies, authors have not reported their results for all 26, and authors have not provided their data after repeated requests. Currently they have not even provided a list of the 26 studies.

And suddenly the BBC article has some explaining to do! And Ivmmeta.com does list all 79 studies, with lots of citations and numbers to boot. A counter-counter-argument against ivmmeta.com requires an even more exhaustive catalog of evidence (which, by the way, plenty of people have provided).

Often it seems like scientific communicators have a low opinion of the average consumer. "Don't overwhelm people with data," I can hear some comms consultant saying. "Use short words and repeat yourself." Gah! Sure, summarize the data, but also provide the data—and make sure you include all of it.

Exhaustive medical communication also needs to be updated frequently. The latest recommendation about Ivermectin use from the WHO was published in March 2021—we've had two more variants and a bunch more Ivermectin trials since then. So if I'm weighing the WHO’s stale recommendation against ivmmeta.com's recommendation—which is updated weekly—it seems like I should put a lot more emphasis on the latter.

And finally: quantitative, exhaustive medical information is no good unless it's accessible. Anyone with an internet connection should be able to discover and understand this information.

Peer-reviewed meta-analyses, for example, fail the accessibility test on two counts. First, they are often literally inaccessible behind publisher paywalls. Academic publishing is an unholy scam, and some researchers are trying to do something about it, but there's still a lot of critical information that's too expensive for the average person to read.

And even if you can find an open-access meta-analysis, it's inaccessible in a second way: it's incredibly boring! Your typical systematic review is a wall of text punctuated by dense tables, flow charts, and forest plots—which nerdier readers might find scintillating, but trust me: the average consumer feels unendurable boredom when faced with a funnel plot.

So good communication is consumer friendly. It doesn't omit technical details (that would violate the exhaustive requirement)—but it uses progressive disclosure to present users with exactly as much information as they need at that moment.

Medical communication can also be inaccessible if it’s condescending. Here’s a prime example from the official FDA Twitter account:

You read that right: the FDA thinks you’re acting like a cow.

Let's imagine for a moment that the FDA article linked in this tweet is a fantastic piece of medical communication (it's not). Who the $&@! is going to click that link? People who think Ivermectin doesn't treat COVID are going to feel smugly superior and keep scrolling (why read an article that tells them what they already know?) and people who do think Ivermectin could treat COVID feel extremely insulted, block the FDA Twitter account, and also keep scrolling. This tweet makes the Ivermectin discourse worse in every possible way. Ugh.

Okay so to summarize: good medical communication should be quantitative, exhaustive, and accessible. Unfortunately, the vast majority of medical communication fails to live up to these standards, and as a result we end up in a situation where lots of people believe things that are contradicted by current evidence.

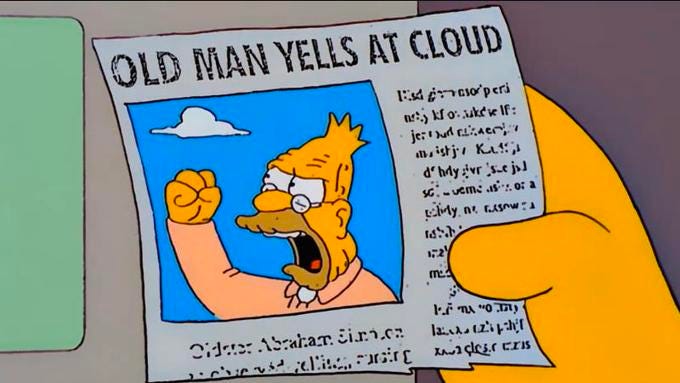

There’s lots of "old man yells at cloud" energy in this post so far.

But I took a few deep breaths and decided that complaining wasn’t really helping, and in a fit of hubris I decided to create a tiny example of the kind of medical communication I envision.

Since using a COVID-related test subject would be way too fraught, I needed to find another medical subject to use as my guinea pig. A good test subject would be:

Interesting

Controversial

Low stakes

So I chose zinc lozenges! If you've ever been to a drugstore you've seen Cold-eeze, Zicam, or store-brand zinc lozenges that purport to shorten the duration of the common cold. Ever wonder if those actually work? It's an interesting subject because everyone gets colds and everyone wishes they were shorter—so if cheap lozenges worked they'd be amazing. It's controversial because the evidence for zinc lozenges is mixed. And it's low stakes because zinc lozenges are relatively harmless and cheap.

So I spent a few hours compiling the existing evidence on zinc lozenges and stitched it together with a bunch of really terrible Javascript.

Here's what I've got so far:

You can play around with it here:

Here's why I like it:

It’s quantitative. There are numbers! Most importantly, the top-line result contains a number: "...zinc lozenges reduce cold durations by X%" (where X depends on your study selection). Knowing how to quantify the effect size of zinc helps you make real world decisions about zinc—like whether it's worth the cost, hassle, and risk of side effects.

It’s exhaustive. I ran the last literature search on February 2, 2022, and I have weekly reminders set to run the search again and update this list with new zinc trials (see Search strategy section of the site for more details). This means I have trials that were published after the last meta-analysis (e.g. Hemilä 2020). And I allow users to play around with all relevant clinical trials, even if some researchers have excluded them from a particular meta-analysis.

It’s accessible. It’s free as in beer! And while I'm certainly not a design expert, it's free of a lot of clutter, ads, and dense prose that a lot of other medical sources have. And (hopefully) it's simple enough to be readable by non-experts, but informative enough to not come off as paternalistic or condescending.

But it definitely has a way to go! Here are some things I'd like to add eventually:

Adverse event data. You can't really make an informed medical decision unless you know the risks of a certain treatment—but right now my zinc page only tells you about possible benefits. Having a section that lists reported adverse events, along with their incidence, would help people understand the tradeoffs involved.

More trial data. I want to add more info about each trial, like

GRADE rating

Preregistration status

Funding source

Better UI. It’s super ugly right now!

It’s a small start, but I think this page is pretty useful for synthesizing the current research on zinc lozenges. What do you think? Helpful? Misleading? Confusing? Simplistic? Send me some feedback via email (tom@tjcx.me) or Twitter (@tomjcleveland—but please, no condescending cow tweets).